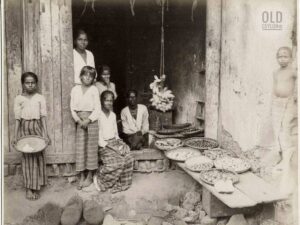

Sri Lanka was colonised by the Portuguese (1597-1658), the Dutch (1658-1796) and the British (1815-1948). When the Portuguese arrived in Sri Lanka, they built a series of coastal forts and seized control of much of Sri Lankas coastline, driving the Sinhalese inland to Kandy and the hill country. There is not much of the original fort they established at Colombo left to see, but it has shaped the whole layout of the city and today the fort area houses many of the Sri Lankan capitals most important buildings. Other Portuguese forts were established all around the coast and interesting examples can be seen at Galle, Matara, Batticaloa, Trincomalee, Jaffna, Mannar and Kalpitya, although some, such as the fort in Galle were developed extensively by the Dutch later. Asides from forts, visitors to Sri Lanka will notice the Portuguese influence is still prevalent in some other aspects of society – in the many Roman Catholics, in the many Portuguese surnames (De Silva, Perera, Medis, etc), in words that have crept into the Sinhalese language and in food (think fantastic cakes and breads).

Sri Lanka was colonised by the Portuguese (1597-1658), the Dutch (1658-1796) and the British (1815-1948). When the Portuguese arrived in Sri Lanka, they built a series of coastal forts and seized control of much of Sri Lankas coastline, driving the Sinhalese inland to Kandy and the hill country. There is not much of the original fort they established at Colombo left to see, but it has shaped the whole layout of the city and today the fort area houses many of the Sri Lankan capitals most important buildings. Other Portuguese forts were established all around the coast and interesting examples can be seen at Galle, Matara, Batticaloa, Trincomalee, Jaffna, Mannar and Kalpitya, although some, such as the fort in Galle were developed extensively by the Dutch later. Asides from forts, visitors to Sri Lanka will notice the Portuguese influence is still prevalent in some other aspects of society – in the many Roman Catholics, in the many Portuguese surnames (De Silva, Perera, Medis, etc), in words that have crept into the Sinhalese language and in food (think fantastic cakes and breads).

As well as developing the Portuguese forts, the Dutch pushed further inland and introduced their own unique architectural style and cultural influence. The Galle fort area has, without question, the most famous examples of Dutch architecture in Sri Lanka, but there are others to be found, such as the old Dutch hospital in Colombo, thought to be the oldest surviving building in the city and now home to stylish boutiques and fashionable restaurants. Like the Portuguese, the Dutch influence can also be seen in many of Sri Lanka’s names – Dutch forenames such as ‘Cornelis’ and ‘Johanna’ are not uncommon among the Sinhalese and place names in Colombo and Galle include ‘Hulft’s Village’, ‘Wolvendaal’ and ‘Leyn Baan Street’. Although the Dutch Calvinist strand of Christianity has taken less hold in Sri Lanka than Catholicism has, aspects of the Roman-Dutch law which were introduced back in 18th century still form an important cornerstone of the Sri Lankan legal system.

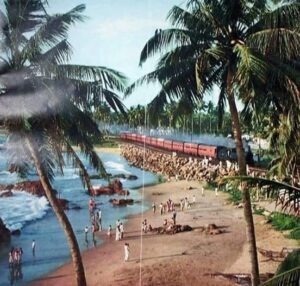

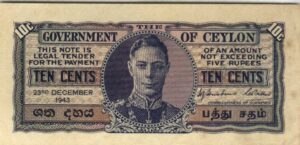

Being the most recent of the three colonisers, it is perhaps unsurprising that the British influence in modern day independent Sri Lanka is the most noticeable. Although Sri Lanka won its independence from the British Empire at the same time as India, in 1948, it remained a dominion of the British Empire until 1972, when its name officially changed from Ceylon to Sri Lanka. It is certainly true that wherever you visit in Sri Lanka nowadays, you will see evidence of British rule. Be it a colonial style government building, a train winding through the hill country, a group of school children or a game of street cricket, you are never far from something that evokes the British Empire.

Much of the infrastructure found in modern Sri Lanka originated from the British colonial rule. The education system is largely modelled on that which the British Christian missionaries introduced and still includes many faith schools (both Buddhist and Christian). Many of the educational qualifications work in the same way and you may, for example, find your guide talking nostalgically about doing his ‘O-levels’. Many schools are still housed in the original British built buildings, as are some official buildings, the Post Office in Nuwara Eliya is a fine example of this, as is the National Museum in Colombo. It is not just the official buildings which remain from British rule, but in recent years some of the beautiful tea planters’ bungalows found throughout the hill country have been lovingly transformed into magnificent world class boutique hotels – see Ceylon Tea Trails, a collection of luxurious colonial style bungalows near Hatton, Stafford Bungalow near Nuwara Eliya or the Rosyth Estate House at Kegalle, to name just a few.

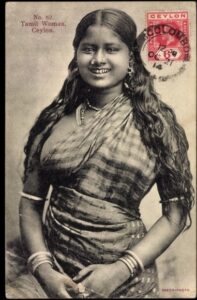

Of course, it would be impossible to write about British influence in Sri Lanka without bringing up tea production. When they took over the hilly region to the southeast of Kandy, the British tested out the fertile land on a number of crops and came to the quick conclusion that this was the perfect terrain to grow tea. British run tea estates of all sizes quickly popped up all over the hill country, producing huge amounts of tea to export to other parts of the empire and beyond. This not only introduced an industry which continues to be very important in modern Sri Lanka, but it has also resulted in a large Tamil population in this part of Sri Lanka as the British brought in thousands of Indian Tamils to work on the plantations.

Whilst there are a few Portuguese and Dutch words that have crept into the Sinhalese language, it was again the British colonisers who had the greatest influence on language in Sri Lanka, with Sinhalese, Tamil and English being recognised as the three official languages. Not only is English taught in all schools, but visitors will find that street signs are in English and the level of spoken English is good in most places, although don’t rely on being able to communicate so well if you’re visiting Jaffna and some of the less visited parts of northern Sri Lanka or other rural parts.

The final point about British colonial influence in Sri Lanka that we wanted to highlight, but by no means the least, is cricket. From large, packed stadia showing international games to schools to beaches to carparks, you are never far from a game of cricket or someone willing to talk for hours about the state of the Sri Lankan national team. Sri Lankan’s love the game of cricket unconditionally, it is a match made in heaven!